by Justin Stein

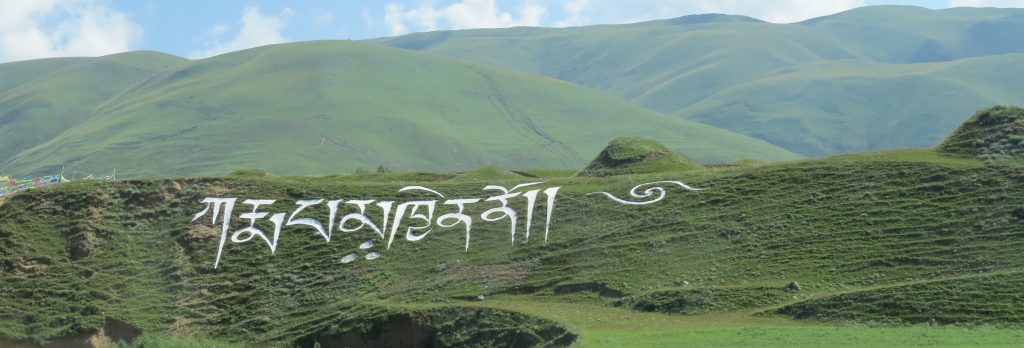

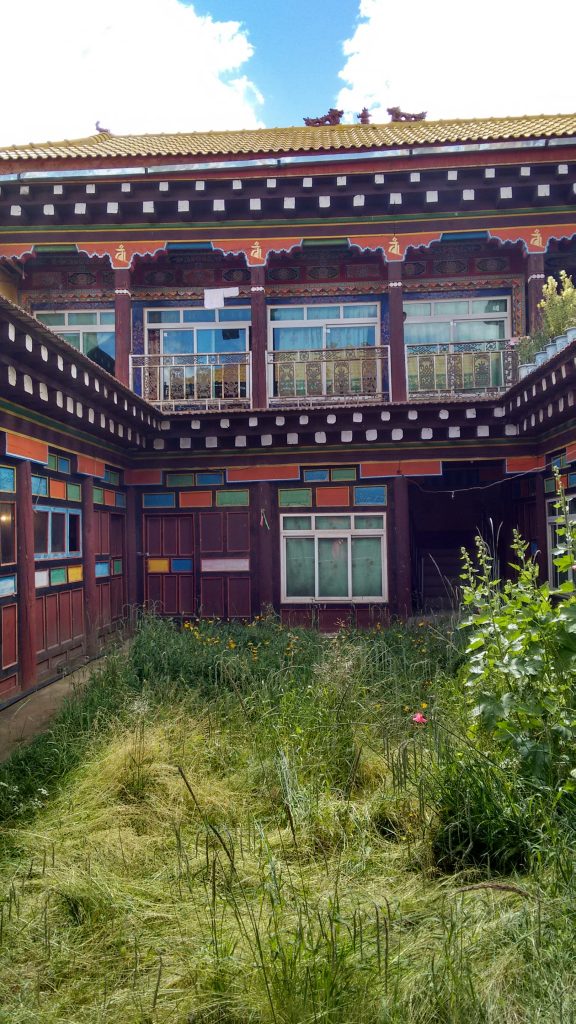

On May 31, His Holiness the 17th Gyalwang Karmapa Ogyen Trinley Dorje opened his first visit to Canada on our campus. Convocation Hall filled with 1500 people who wanted to hear the head of one of the largest schools of Tibetan Buddhism and the incarnation of the Bodhisattva of Compassion. Born in 1985 to a traditional nomadic family in the high mountains of western Kham in the southeastern part of historical Tibet, Ogyen Trinley Dorje was recognized at the age of seven as the next Karmapa. He was enthroned in the Karmapa’s traditional seat, where he resided until he escaped to India in 2000. In the last ten years, His Holiness has established groundbreaking initiatives in the Tibetan Buddhist world, promoting environmental sustainability, vegetarianism, and full monastic ordination for women.

His Holiness gave a teaching sponsored by the Ho Centre, titled “Mindfulness and Environmental Responsibility.” His Holiness opened by reflecting on the site of Toronto as a gathering place for diverse peoples. His Holiness contrasted Canada’s multicultural vision with one of immigrant assimilation, expressing appreciation for the way Toronto’s immigrant communities maintain intergenerational cultural identities and serve as ambassadors to their cultures.

Audience members posed difficult questions that bridged the psychological and the political, and His Holiness’ responses, mostly given through his uncommonly erudite and eloquent personal interpreter, were uniformly clear and inspiring. When asked about how to enact change in the world, His Holiness explained his path to vegetarianism. “I didn’t just like eating meat, but I loooved eating meat,” he joked about his youth growing up in a Tibetan nomadic community. But, he explained, as he received his Dharma transmissions and reflected on compassion for sentient beings, meat appeared differently. He eventually stopped eating it and began advocating vegetarianism as a commitment to decreasing suffering. He suggested that social change, similarly, happens through individual reflection on how our ingrained habits are tied to oppression, commitments to change one’s own habits, and involvement in movements within one’s own community.

The next day, I was among a group of Buddhist Studies students and faculty who, along with students and faculty from the Centre for Indigenous Studies, Emmanuel College, and the School of the Environment, were invited to a private luncheon dialogue on “Sustainability and the Sacred” with His Holiness. Thirty of us sat in a square of tables in the main hall of the Multi-Faith Centre, and each able to ask questions directly to His Holiness.

Sean Hillman, a bioethicist and PhD candidate in Buddhist Studies, asked about the applicability of the Buddhist ethical doctrine of non-harm to the practice of medical assistance in dying, which became available to Canadian patients in 2016. His Holiness said that literal interpretations of the teachings on the Bodhisattva practice of generosity clearly indicates that it is not permissible to give poison to others, but other reflections could complicate this interpretation. Another saying of the Buddha’s dictates that, at times, what is proscribed must be weighed against what is needed. This suggests that, in extraordinary circumstances, the most ethical action could be something that is generally forbidden. For example, there is a Jātaka story in which the Buddha, in a previous incarnation as a ship captain, killed someone because he saw it was the only way to prevent hundreds of other deaths. He concluded more dialogue between the practice’s supporters and detractors is needed to determine that all perspectives are being understood.

I asked about whether the Buddhist concept of transforming poison into medicine (presented in the Lotus Sutra) could suggest a possible place for negative emotions, particularly anger, in movements for social justice. His Holiness said that anger plays a large role in activism, particularly environmental activism, but this anger can lead to a number of negative outcomes in addition to serving as a healthy spark to righteous action in the face of injustice. However, emotions, he warned, are fleeting, and when they go, the resulting sense of powerlessness can lead to burnout or depression. Thus, successful action comes from combining emotional impetus with planning and preparation to sustain efforts into the future. As His Holiness’ visit coincided with the announcement that the U.S. was pulling out of the Paris climate agreement, I found it reassuring to hear that anger could be a natural response to negative events in the world even if it is insufficient to carry a lasting movement.

It was a great honor to have the Karmapa visit the University of Toronto and provide profound teachings so relevant to our lives. It was particularly inspiring to hear how His Holiness is putting his principles into action, using his office to personally support Buddhist temples and monasteries’ development of sustainability plans, as well as his involvement to improve gender equality by instating the full ordination of Tibetan Buddhist nuns. It was remarked upon several times during his visit that the title “Karmapa” literally denotes the one who carries out Buddha-activity in the world and his interactions at the University of Toronto reinforced the claim that he is actively engaged with embodying these religious ideals in the public sphere.

Below see the full “Mindfulness and Environmental Responsibility” talk

s come close: for instance, the Śivapūraṇa and Viṣṇupūraṇa have prefaces about the virtues of the texts, and how they should be used, but from the paratextual studies perspective, this is still a paratext: not incorporated into the body of the text in the same way the passages found in Mahāyāna passages are. This really emphasises a point that needs to be understood about these passages in Mahāyāna sūtras, they are not paratextual, but act like paratexts: they are interspersed throughout the text and are not prefatorial or introductory. My theory on why this is so, is that prefaces and introductions, being paratextual, may be discarded in the process of textual transmission, but if hardwired into the text itself, they are less likely to suffer this consequence, both making the passages more resilient parts of the whole and underlining their importance to the redactors of the Mahāyāna texts.

s come close: for instance, the Śivapūraṇa and Viṣṇupūraṇa have prefaces about the virtues of the texts, and how they should be used, but from the paratextual studies perspective, this is still a paratext: not incorporated into the body of the text in the same way the passages found in Mahāyāna passages are. This really emphasises a point that needs to be understood about these passages in Mahāyāna sūtras, they are not paratextual, but act like paratexts: they are interspersed throughout the text and are not prefatorial or introductory. My theory on why this is so, is that prefaces and introductions, being paratextual, may be discarded in the process of textual transmission, but if hardwired into the text itself, they are less likely to suffer this consequence, both making the passages more resilient parts of the whole and underlining their importance to the redactors of the Mahāyāna texts. oined by their very skilled daughter Emilia, who usually won! The food was a mixture of Newar and Italian cuisine, and was always more than satisfying. Newar food was very agreeable for me, as it is not too spicy, dry, and quite mild overall. The exception would be beaten rice, baji, to which I never managed to get used.

oined by their very skilled daughter Emilia, who usually won! The food was a mixture of Newar and Italian cuisine, and was always more than satisfying. Newar food was very agreeable for me, as it is not too spicy, dry, and quite mild overall. The exception would be beaten rice, baji, to which I never managed to get used. f the rite was in Kathmandu rather than Lalitpur was that it was a very sacred location. It may also have been an opportunity for the Bajrācārya Pūjāvidhi Adhyayan Samiti to get in touch with the wider public outside of Lalitpur. The rite took place on Friday, the 10th of May, the full moon day (Pūrṇimā) of the month of Caitra, and its official name was the Nava Sūtra Pāṭha, or reading of the nine sūtras. It was paired with a rite called the Saptavidhānottara, or the performance of the seven higher rites—a series of ritual offerings, involving complex mudra choreography, representatives of the five Buddhas, and a massive maṇḍala. These rites had separate sponsors, but according to one specialist, Deepak Bajracharya, were done on the same day on the same location because it is difficult to get so many priests free on the same day. As for the priests who participated, the rite involved 108 Vajrācārya from not only Lalitpur, but also Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, Thimi, Kirtipur, and Bungamati. While the main sponsors were from Lalitpur, the other supporting sponsors included many Buddhist devotees from around the world, including Taiwan.

f the rite was in Kathmandu rather than Lalitpur was that it was a very sacred location. It may also have been an opportunity for the Bajrācārya Pūjāvidhi Adhyayan Samiti to get in touch with the wider public outside of Lalitpur. The rite took place on Friday, the 10th of May, the full moon day (Pūrṇimā) of the month of Caitra, and its official name was the Nava Sūtra Pāṭha, or reading of the nine sūtras. It was paired with a rite called the Saptavidhānottara, or the performance of the seven higher rites—a series of ritual offerings, involving complex mudra choreography, representatives of the five Buddhas, and a massive maṇḍala. These rites had separate sponsors, but according to one specialist, Deepak Bajracharya, were done on the same day on the same location because it is difficult to get so many priests free on the same day. As for the priests who participated, the rite involved 108 Vajrācārya from not only Lalitpur, but also Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, Thimi, Kirtipur, and Bungamati. While the main sponsors were from Lalitpur, the other supporting sponsors included many Buddhist devotees from around the world, including Taiwan. e performance of another rite involving the Navagrantha. This time it was the ritual recitation of the Lalitavistara Sūtra, the Mahāyāna version of the life of the Buddha up to his awakening. This was a unique occasion as the rite was sponsored and attended by Theravāda monks originally from Thailand who are now working for Dhammachai International Research Institute based in Sydney, Australia. One of these monks, Phra Weeachai, explained that they were in Nepal to collect manuscripts, but were invited by Naresh Man to observe the pūjā.

e performance of another rite involving the Navagrantha. This time it was the ritual recitation of the Lalitavistara Sūtra, the Mahāyāna version of the life of the Buddha up to his awakening. This was a unique occasion as the rite was sponsored and attended by Theravāda monks originally from Thailand who are now working for Dhammachai International Research Institute based in Sydney, Australia. One of these monks, Phra Weeachai, explained that they were in Nepal to collect manuscripts, but were invited by Naresh Man to observe the pūjā. instance, the chariot is met by a smaller version pulled by teenage boys, and at one point one of the Kumārīs, or girl goddesses, exits from her shrine to greet the chariot as it passes. This year, not all of the electrical cables had been cut across the streets, meaning that at one point, the smaller chariot had to force its way through the wires, forcing everyone who was standing behind that wire have to jump out of the way to dodge the cable! The cable snapped off each pole down the street, to what seemed to be the entire length of the cable around a bend in the street.

instance, the chariot is met by a smaller version pulled by teenage boys, and at one point one of the Kumārīs, or girl goddesses, exits from her shrine to greet the chariot as it passes. This year, not all of the electrical cables had been cut across the streets, meaning that at one point, the smaller chariot had to force its way through the wires, forcing everyone who was standing behind that wire have to jump out of the way to dodge the cable! The cable snapped off each pole down the street, to what seemed to be the entire length of the cable around a bend in the street. one side by a sheer drop of thousands of feet. The driver said that these roads were no problem compared to those going up to Gorkha! At the top, we visited a Tamang temple which was being rebuilt, after being devastated in the earthquake last year. The original temple had been built with mud brick and was being replaced by one with steel reinforcement and concrete with funding from BLIA. On another mountain peak was Shree Tapeshwor Higher Secondary School, which had been rebuilt entirely with BLIA funds. The view from the mountain was quite breath-taking, and after going down into the valleys for lunch, we proceeded back to Banepa, where we observed the shelters that had been built for urban families who had lost their homes in the earthquake. At that point, the majority of the people who had benefited from these shelters had been rehoused, meaning the project, overall, was a success. One can only pray that the next earthquakes are weaker, and the buildings are made more resilient.

one side by a sheer drop of thousands of feet. The driver said that these roads were no problem compared to those going up to Gorkha! At the top, we visited a Tamang temple which was being rebuilt, after being devastated in the earthquake last year. The original temple had been built with mud brick and was being replaced by one with steel reinforcement and concrete with funding from BLIA. On another mountain peak was Shree Tapeshwor Higher Secondary School, which had been rebuilt entirely with BLIA funds. The view from the mountain was quite breath-taking, and after going down into the valleys for lunch, we proceeded back to Banepa, where we observed the shelters that had been built for urban families who had lost their homes in the earthquake. At that point, the majority of the people who had benefited from these shelters had been rehoused, meaning the project, overall, was a success. One can only pray that the next earthquakes are weaker, and the buildings are made more resilient.