A research report by Siew Han Yeo, doctoral student in the Department of History

In June-July 2019, thanks to the generosity of the Robert H. N Ho Center for Buddhist Studies Student Travel award, I was fortunate to travel to Mandalay for a research trip, I left for Mandalay on July 11 and spent three weeks in Mandalay reading the collections at the Ludu Library. While there, I was able to consult many primary source materials, both in Burmese and English, including twentieth-century published books, colonial reports, journals, books, and newspapers published in Mandalay that I have not otherwise seen at the Yangon University Central Library or the National Archives Department in Yangon, my other two research sites in Myanmar.

Back in Yangon, I have began to translate select sections of these materials with the help of Su Htwe, my Burmese teacher. Su Htwe and I have translated numerous newspaper reports from the Burmah Herald, Thuriya Magazine (Mandalay edition), Burma Journal, and the Hanthawaddy Weekly Review – mostly on topics related to the Chinese community in Burma. My focus on newspaper reports have allowed me to familiarize myself with the Burmese literary scene of the late nineteenth and twentieth-century Burma. Burma/Myanmar has a particularly exciting literary history – but there is little English-language scholarship that discusses the vibrant history of colonial Burma’s literary scenes. I will be leaving Yangon to return to Canada in early October.

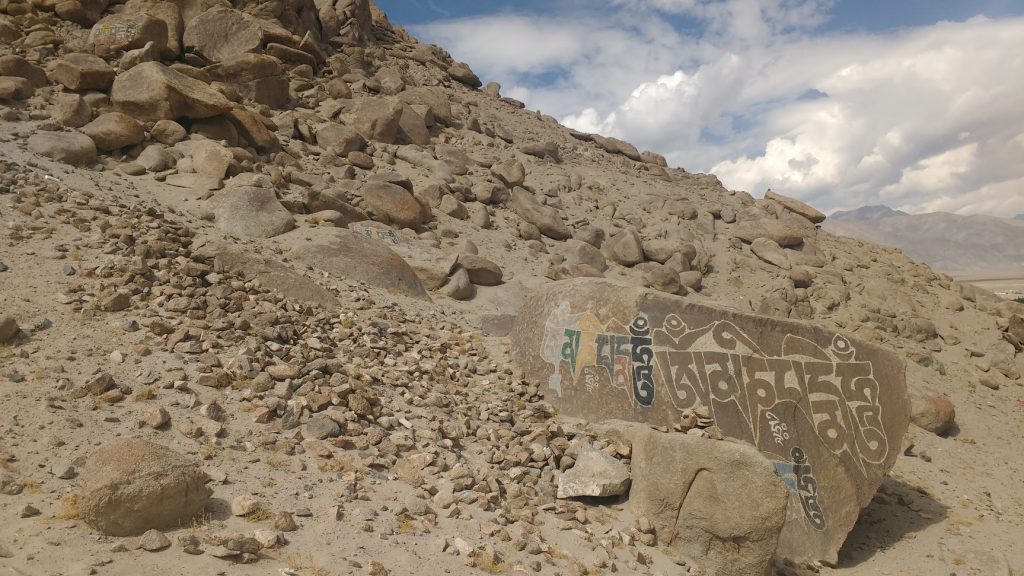

My plan was to study Tibetan whilst staying in community of Choglamsar, about 10 kilometers down the road, during which I would continue to investigate sacred places and landscapes around there. Choglamsar is home to native Ladakhis as well as many Tibetan refugees and Kashmiris. Around that town it was particularly interesting to observe the formations of a Buddhist environment in the gnarled desert landscape.

My plan was to study Tibetan whilst staying in community of Choglamsar, about 10 kilometers down the road, during which I would continue to investigate sacred places and landscapes around there. Choglamsar is home to native Ladakhis as well as many Tibetan refugees and Kashmiris. Around that town it was particularly interesting to observe the formations of a Buddhist environment in the gnarled desert landscape.