By Damien Boltauzer

In the summer of 2018 I set out to the Himalayan regions of Himachal Pradesh and Ladakh in north-west India. My aim was to investigate spaces and geographies sacred to the Buddhists of those regions. My approach was to be comparative: I would visit Rewalsar in central Himachal Pradesh, Keylong in the far north of that state, and Leh/Choglamsar in Ladakh.

Dharamshala and Tso Pema

The highway emptied out of Delhi and soon began to graduate into higher territories winding up to Dharamshala in the foothills Himachal, whilst I was dozing on a sleeper bus storming through the night. To start off my trip, I wanted to visit the seat of the Tibetan government in exile – a sacred space of its own within field of the 14th Dalai Lama. That week he was giving a teaching and a tantric empowerment of the Bodhisattva of wisdom and learning, Manjushri. Being a student and much in need such power, I took the empowerment before heading deeper into the mountains.

My next stop was the village of Rewalsar, a place that I read about in a travel guide for Ladakh which was described as “an interesting detour”[i] about an hour away from the large town of Mandi. I took the bus out from Dharamshala in the early morning and was in Mandi by mid-afternoon; there I got on a smaller bus which went down a bumpy dirt road into the hills for one more hour. I really had no idea what I would find, but it turned about to be most fulfilling. For a student of religion, Rewalsar is a magnificent place: a village surrounding a small green lake which is sacred within Vajrayana Buddhist, Sikh, and Saiva traditions. Another name for the place is Trisangam, meaning “three holy communities”[ii].

Each of the traditions have their own texts and narratives in which the sanctity of the lake can be found. For Vajrayana Buddhists, this history takes place in the life story of Padmasambhava, the tantric master responsible for spreading the Dharma through the Himalaya and Tibet. In that text, Padmasambhava has recently met his consort Mandarava who is the daughter of Arshadhara, the king of the Sahor country. He and Mandarava go to the city to beg for alms:

While doing that the people became envious and said, “This is the stray foreign mendicant, who in the past killed the males and coupled with the females. He has carried off the king’s daughter and adulterated the royal caste. Again, he will create havoc; he must be corrected!”.

Saying this, the people gathered sandalwood with a dray of oil for each load of wood. After that, they burned Master Padma and his consort in the center of a village.

Normally, when people were burned, the smoke would cease after three days, but now even after nine days the smoke did not stop. As people came for a closer look, the fire blazed up, burning the entire royal palace. The oil had turned into a lake, with the inner part covered by lotus flowers. Upon an open lotus, in the middle of the lake, Master Padma and his consort sat fresh and cool. [iii]

‘Tso Pema’ (Lotus Lake) is the Tibetan name of the lake. It is an important site of pilgrimage for pious Buddhists, especially those of the Nyingma lineages. I was told that especially in the winter months pilgrims converge there in large numbers, waiting out the cold winter in the north. Presently there are at least five Buddhist monasteries around the lake, and the most dominating presence in the village is a gigantic statue of Padmasambhava which looms over the village. The lake is also sacred to Saiva Hindus, it is mentioned (along with many other Himalayan regions) in the Skandha Purana. That text also speaks of the visitation to the lake by the holy man Lomas. Similarly, the region was visited by Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Guru of Sikhism, and for that reason it is a pilgrimage site for those of certain Sikh traditions.

As soon as I arrived in Rewalsar I found a simple room at one of the Buddhist monasteries, and I began to absorb the multiple cultural layers and processes which thrived around the lake. The narrative elements of Rewalsar were one aspect of the site and its culture; there is also that which is not articulated in words but which endures within built and natural environment there. This material dimension of the site is practiced with the body and senses, as well as through iterations of stories; it murmurs in images and sounds. It might be said that the lake constitutes the ritual (as well as historical and mythological) center of the village: all day, pilgrims, tourists, and local people can be seen doing ‘kora’ – circumambulations around the lake. There are numerous religious structures: gompas (Buddhist monasteries), mandirs (Hindu temples), a large gurdwara (a Sikh space of worship), and a Jain temple built around the lake. Looming above the all the surrounding temples and residences is a gigantic statue of Padmasambhava. A rich conversation can be read in the multiple structures and their relationships to each other, speaking the story of the sacred space in an architectural code.

Part of my research was to do kora and speak with the circumambulators. To some, these walks were a form of religious engagement with the lake. One or two pious Tibetans were doing full prostrations in their kora. Part of the kora process involves visiting shrines and making offerings, or turning prayer wheels and releasing mantras into the wind. Other people were simply ‘going for an evening walk’. An especially engaging element of the environment is what could be described as the ritual soundscape. Doing kora, one can hear a constant parade of hymns, bells, chimes, gongs, and the rich aural dimensions of Vajrayana liturgy. Bellow my room at the monastery were three large mani-wheels, the turning of which caused a bells to resound at variated intervals, creating interesting rhythms which can be heard here:

Garsha

My next stop was in the far northern reaches of Himachal, in the high mountain region of Lahaul, a day and a half’s journey upon government busses from Rewalsar.

I wanted to investigate an annual circumambulation event of a holy mountain near the village of Keylong. According to an article written in the 1990’s, this event occurred in June; it turned out that this year it was to happen in September and by then I would be elsewhere. Fortunately, I was able to interview the organizers of the annual circumambulation, the Young Drukpa Association, and to learn about the kora event which is publicised as an Eco Pad Yatra.

This kind of event follows in the tradition of those organized by H.H. Gyalwang Drukpa, the head of the Drukpa lineage, who has been leading these kinds of ecological pilgrimage events for over ten years[iv]. The event held in Keylong was led by Kunga Rinpoche, who travelled with a group of monastic and lay Buddhists on a kora of the Holy mountain of Dribu Ri. This modest but holy mountain is revered as an abode of the tantric deity Chakrasamvara. There are many caves in which old masters and tantric heroes practiced, such as Nagarjuna and the Siddha Orgyenpa[v]. The mountain itself is named after the Mahasiddha Vajra-Ghantapa, who is Dorje-Drilbupa in Tibetan. It is said that Drilbupa meditated upon the mountaintop and reached the highest enlightenment there. The peak is now considered to be his “eternal residence” (26)[vi].

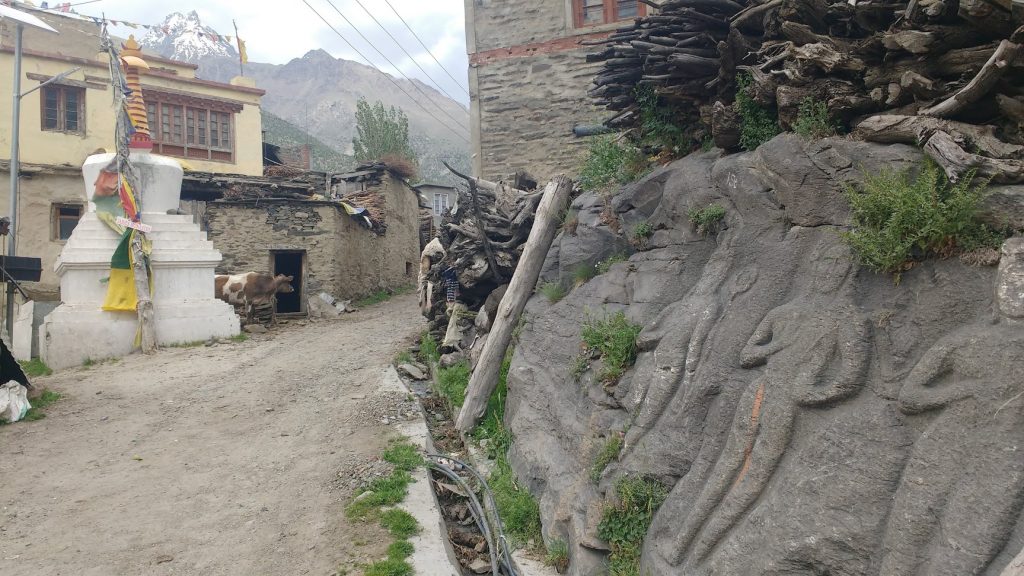

My days in Keylong were spent investigating the numerous places described in a book published by the Young Drukpa Association, entitled Garsha: Heartland of the Dakinis (2011). Pilgrimage guidebooks in Tibetan Buddhism are an old tradition; this particular book might be considered as part of this tradition – now in glossy coloured print form. The text provides detailed descriptions of the many sacred caves, relief sculptures, charnel grounds, and important ancient monasteries, shrines, and stupas in the region, as well as historical information on the whole sacred geography known colloquially as Garsha.

The area is thought to be a potent land of spiritual power, an earthly locus of the sambhogakaya Heruka, and home to numerous Dakinis. The land is charged with the tantric practices of many old masters, and one’s own practice here can be accelerated by such presences. One morning I rose early and, with a local guide, performed a circumambulation of the mountain. We passed through magnificent and stark terrain, rising higher and higher to the peak upon which was a shrine and many prayer flags.

After spending some time there eating sandwiches, we descended again, diagonally across the mountain so as to reach important mediation caves and a gompa on the other side. Another day I visited the Guru Ghantal Gompa, named after Mahasidda Ghantapa, in which one can find a unique shrine with ancient images. To get there, it is necessary to hitchhike on the highway south of Keylong back toward Manali for about 15 minutes until crossing the Bhagi river. Then you can walk ten minutes up the mountain to Tupchilling monastery at which you can ask a resident monk for the key to Guru Ghantal which is another hour up the mountain. When I was there, a local man had already taken the key and was up at the mysterious little gompa on the mountainside. He showed me around and explained his family’s tradition of visiting the shrine at times of confusion.

Ladakh

Journeying further north for one full day upon the grimy Himachal government bus, I finally reached the administrative center and tourist hub of Leh in the Ladakh region of Jammu and Kashmir. The road passed through vast, rugged beauty of the Himalayas and into the arid otherworld of Ladakh.

My plan was to study Tibetan whilst staying in community of Choglamsar, about 10 kilometers down the road, during which I would continue to investigate sacred places and landscapes around there. Choglamsar is home to native Ladakhis as well as many Tibetan refugees and Kashmiris. Around that town it was particularly interesting to observe the formations of a Buddhist environment in the gnarled desert landscape.

My plan was to study Tibetan whilst staying in community of Choglamsar, about 10 kilometers down the road, during which I would continue to investigate sacred places and landscapes around there. Choglamsar is home to native Ladakhis as well as many Tibetan refugees and Kashmiris. Around that town it was particularly interesting to observe the formations of a Buddhist environment in the gnarled desert landscape.

Ladakhi and Tibetan Buddhists articulate their religious culture on a geographical level with no ambiguity: from any high point above the town, one can see multiple golden roofs of the monasteries, prayer flags like cobwebs binding the structures, and stupas dotting the environment in every direction.

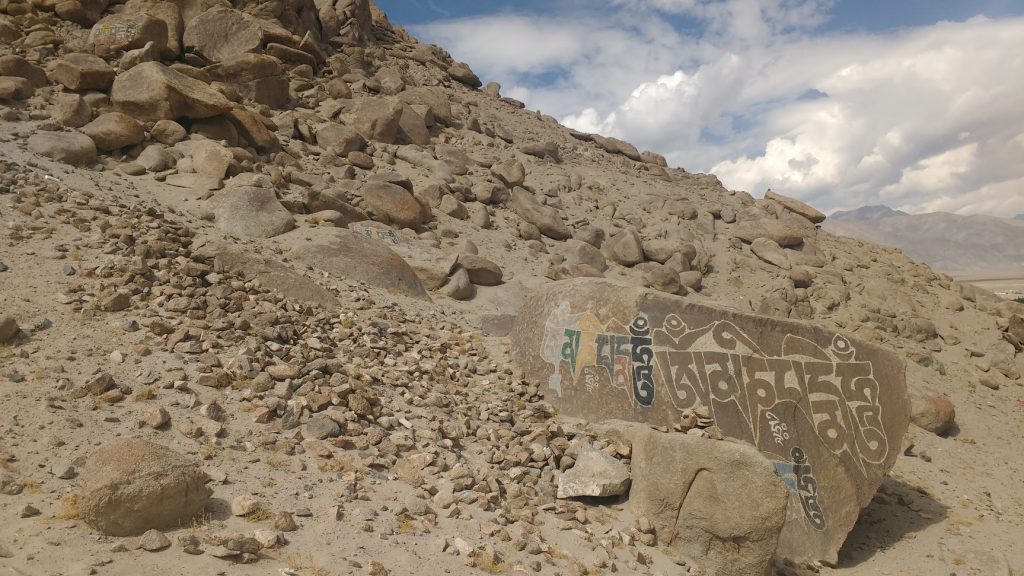

In Ladakh, a notable presence is that of ‘mani stones’ – large rocks or cliff faces with the carving and painting of a mantra, usually that of Om Mani Padme Hum, the mantra of Avalokitesvara. There are ‘mani walls’, which are long stone walls, three or four meters wide which might be described as monuments rather than walls. The tops of these structures serve as a platform for hundreds of small, hand carved mani stones which are often left as offerings. I was told by one informant that mani stones and walls are constructed with the hope that the souls of the dead will encounter the inscription of the mantra, thereby influencing them and neutralizing any potential harm upon the lives of the living. Just outside of Choglamsar there are hundreds of such carvings in the vicinity of a scraggly rock where the dead are cremated on platforms on the hill side.

Perhaps the most dominant cultural element of the Ladakhi landscape is the stupa which is truly ubiquitous in Ladakh. On will see small stupas dotting the landscape, such as the vast field of them near the old palace of Shey, just south of Leh and Choglamsar. Stupas were originally built as monumental reliquaries for the bodily remains of the Buddha after his paranirvana. Since then, they have taken on various functions. Many of the stupas around Ladakh are votive stupas built in honour of the dead, or they might have been built by convicted criminals as part of their punishment. Stupas are erected at the entrances of any town or village for apotropaic purposes, and there are also many within the confines of settlements. In the midst of the town of Leh one will find several large stupas, the ritual engagement with which is a matter of daily life: the pious will pass them always on the right, or perform a few circumambulations as they go about their daily activities. In this sense, ‘sacred space’ is interwoven with that of the profane, prompting interesting theoretical speculation about the organization and nature of space in these cultural contexts. For pious Buddhists, stupas are objects of devotion to which prayers are offered; it is not uncommon to see people gazing with deep intent upon these presences.

They are also important fields of merit. Circumambulation for purposes of merit making is a normative element of daily Buddhist practice in Ladakh. In the park next to the Dalai Lama’s residence in Choglamsar, a friend of mine told me that if it were possible to do 108 koras around the stupa, then I might secure an auspicious re-birth. It is very common to see Ladakhis and Tibetans do exactly this, especially in morning and evening times, and often whilst reciting mantras and counting the beads upon a mala. Small stones are placed on the corner of the stupa to keep the count of passes. The stupa was described to me by this informant as ‘god’ – going around them, then, was an act of encircling god. They are commonly described as representations of the Buddha’s enlightened mind.

My trip to India in the summer of 2018 was a fantastic journey into the spaces of the Buddhists (and other religions) of that area. Through a comparative approach, I was able to notice the nuanced differences and similarities in manifestations of religious culture upon spatial terms as I travelled from site to site. I was also able to develop a deeper understanding of what ‘sacred space’ is: something expressed in multiple voices and material manifestations. The trip as enabled me to go deeper into this most rich of topics and to identify at least three sites which would be excellent for future research.

I would like to thank the Faculty of Arts and Sciences for the generous 2018 Excellence Award and to Frances Garrett for making the trip possible. Also, big thanks to Frances and Matt and the Himalayan Borderlands project for funds and support.

Damien Boltauzer is a fourth year Religion studies and Anthropology major. All photos and audio recordings in this article are his own.

[i] Partha S Banerjee. Ladakh, Kashmir, Manali: The Essential Guide. Calcutta: Milestone Books, 2014. 21,

[ii] http://www.rewalsar.com/

[iii] Yeshe Tsogyal. The Lotus-Born: The Life Story of Padmasambhava. Boston: Shambhala, 1999. 54-6.

[iv] See http://www.padyatra.org/

[v] Garsha Young Drukpa Association. Garsha, Heart Land of the Dakinis. Keylong: YDA, 2011. 29.

[vi] Ibid., 26.